The Philosopher as Clown & the Clown as Philosopher: Nietzsche & Oscar Wilde

philosophy·@yahialababidi·

0.000 HBDThe Philosopher as Clown & the Clown as Philosopher: Nietzsche & Oscar Wilde

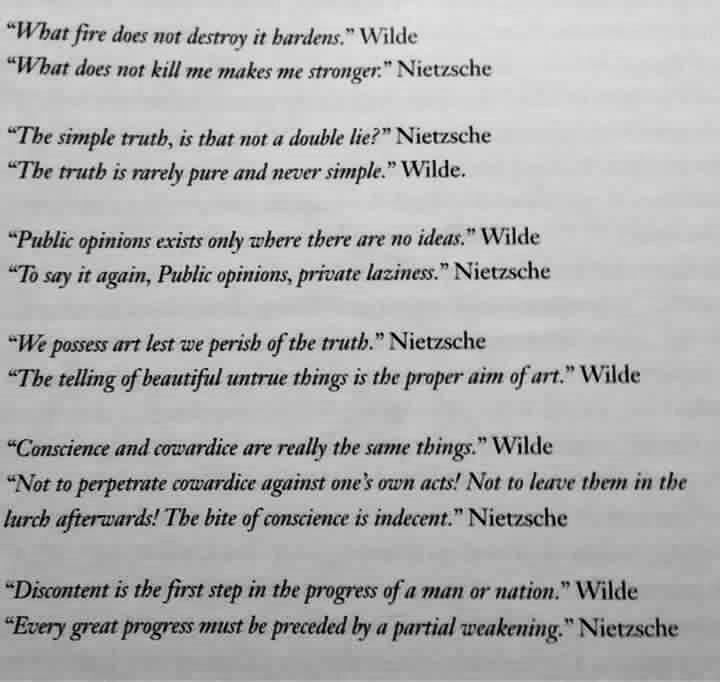

<center>https://simplycharly.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Oscar-Wilde.jpg</center> <center></center> As a continuation to the post I shared earlier, today, on [The Importance of Play](https://steemit.com/fun/@yahialababidi/the-importance-of-play-a-manifesto-of-sorts), I thought a few words about my early influences in literature and philosophy might be apt :) I was deeply drawn, as a voracious, questing teenager, to the work/worldview of Oscar Wilde and Friedrich Nietzsche. I realize, to some, these two might appear to be worlds apart but, for me, they were so close as to seem twin souls. Nietzsche christened his approach *Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft*, which means ‘the joyful science’. It is a worldview in praise of light-heartedness or esprit (witty intelligence). Wilde shared in this playful philosophy which advocated exuberance, buoyancy and a sustaining sunny humor. (Neither was averse to a little playful malice, as well.) They both retained to a high degree the childlike faculties of wonder, joy, and belief in the impossible. This is evidenced in Wilde’s many improbable utterances and his delightful persona of boyish immaturity, as much as in his enchanting short stories for children. The Argentine poet and author, Jorges Luis Borges, spoke of Wilde’s ‘invulnerable innocence’. Similarly, in *Beyond Good and Evil*, Nietzsche defines mature manhood as “that means to have rediscovered the seriousness one had as a child at play.” Along with their child-like innocence, Nietzsche and Wilde’s ‘philosophies’ also represented irreverence, mental/verbal play, and the license to poke fun. *** <center></center> *** “Not by wrath, but by laughter, do we slay. Come, let us slay the spirit of gravity” – thus spake Nietzsche’s *Zarathustra*. In a letter, Nietzsche put it still more mischievously: “I hang a little farcical tail on to the most serious things.” This is a sensibility amply echoed by Wilde: “Life is too important to be taken seriously” as he writes in *Lady Windermere’s Fan*. In the final equation, their answer to profound problems was a stylistic one: aesthetics over ethics. To achieve this, they often found it necessary to return to the surface of things. ***Worlds of Appearances*** Above all, Nietzsche and Wilde were great lovers of life, anachronistic Greeks in their adoration of the sun as life-force and their heady vitalist philosophies sensually imbued with a this-worldly spirituality. Likewise, in their deep belief in the wisdom of the body they echoed the Ancient Greek ideal of the dependence of a healthy mind on a healthy body: >“Oh, those Greeks! They knew how to live. What is required for that is to stop courageously at the surface, the fold, the skin, to adore appearances, to believe in forms, tones, words, in the whole Olympus of appearance. Those Greeks were superficial – out of profundity.” This is not Wilde waxing poetic, but Nietzsche waxing philosophic. Of course, this is also the very same aesthetic philosophy Wilde championed: “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances” (*Picture of Dorian Gray*). Moreover, refinement and taste were prized: “All of life is a dispute over taste and tasting,” Nietzsche has *Zarathustra* say. Such an aestheticism was not only an interpretation of life, but a philosophy for life. *** <center>https://www.elespectador.com/sites/default/files/lou_2.jpg</center> *** Nietzsche and Wilde may have also been *superficial out of profundity* in yet another way, if we allow that their preference for appearances may have been informed by Kant’s skepticism propounded in his *Critique of Pure Reason* (1781). According to this doctrine, we never know things as they are, but only as they appear to be. In this context, their resolve to stop courageously at the surface might not seem so unwise. On another level, according to Alexander Nehamas’ study of Nietzsche, *Life as Literature*, Nietzsche’s aestheticism entailed a tendency for him to view the world in general as a work of art, and as a literary text in particular, populated by literary characters, including himself. Reading and writing were Nietzsche’s substitutes for living and loving, and he lived for and through the written word, as well as learned from and argued with books. Nehamas writes, “his use of and emphasis on style is itself part of his effort to undermine the distinction between form and content in life as well as writing.” Merging life with literature was second nature to Wilde too, who openly admitted to performing his life. He felt life imitated art far more than vice versa, and said to Andre Gide, “My life is like a work of art.” And although as a wit about town he certainly got out more than the reclusive Nietzsche, he confessed in De Profundis: “I treated art as the supreme reality and life as a mere mode of fiction.” Or, as he has Gilbert argue in The Critic as Artist, “When a man acts, he is a puppet. When he describes, he is a poet.” There is much of Nietzsche within this verbal universe, affirming the supremacy of language, reclaiming power from fate through eloquent and articulate expression. In Nietzsche we have the philosopher as performance artist, communicating in jokes, riddles, parables, poems, songs or aphorisms. In Wilde, it is the artist as performing philosopher, having made “art a philosophy and philosophy an art” as he wrote in De Profundis. Or, in the uncharacteristically lavish praise of the usually cantankerous George Bernard Shaw: >In a certain sense Mr Wilde is to me our only thorough playwright. He plays with everything: with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and audience, with the whole theatre” (reviewing Wilde’s An Ideal Husband in the Saturday Review, January 12, 1895). Following Wilde’s death, his friend Max Beerbohm wrote: “He came as a thinker, a weaver of ideas… Theatrical construction, a sense of theatrical effects, were his by instinct” (Saturday Review, December 8, 1900). It is remarkable, given how alike they are in style and philosophy, that the two contrarians (who were contemporaries, born a day apart and passed the same year, 1900) never met or even read one another! You can see for yourself their striking similarity in some of their quotes I gathered, below, where it is difficult to determine which of them is speaking: *** <center></center> *** ©Yahia Lababidi <center></center> (Images: [1](https://simplycharly.com/facts/10-things-might-not-know-oscar-wilde/), [2](https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/cultura/lou-andreas-salome-la-inteligencia-de-un-aguila-y-la-fuerza-de-un-leon-articulo-733234))