The Problem of a Steadily-Increasing Minimum Wage

life·@youdontsay·

0.000 HBDThe Problem of a Steadily-Increasing Minimum Wage

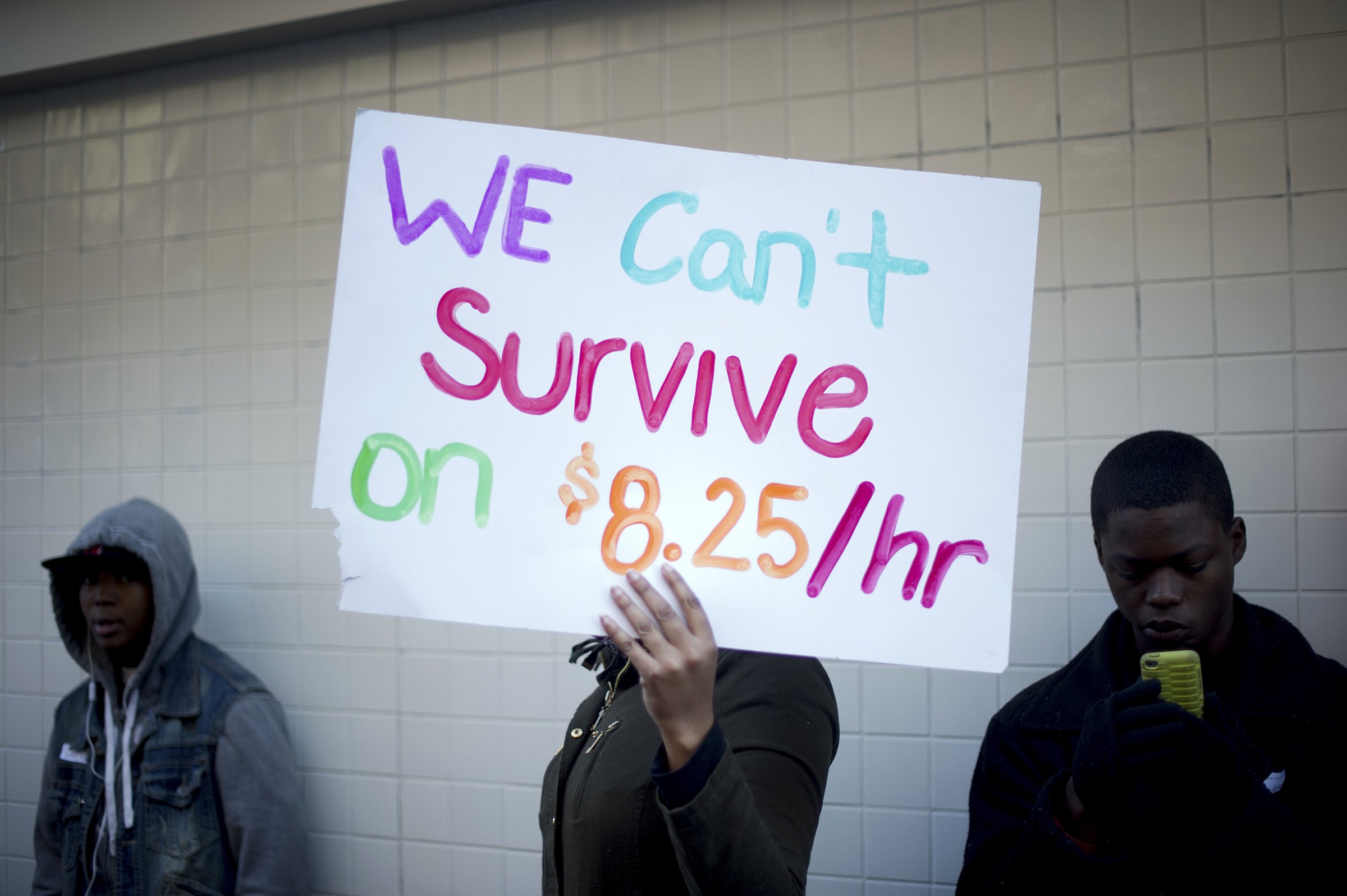

<center>http://cdn07.allafrica.com/download/pic/main/main/csiid/00420447:6b1ad733ef309e9c38e6063957e9c968:arc614x376:w614:us1.png</center> For many it seems to be common sense that increasing the minimum wage would be an effective means of combating poverty and providing relief for hard-working families. The underlying logic is that a higher wage entails a higher salary, and thus raising the minimum wage should allow any motivated person the opportunity to find and sustain a job that will pay for their food, rent, and utility bills. Bill Clinton once said, “It's time to honor and reward people who work hard and play by the rules... No one who works full time and has children should be poor anymore” (Sabia 592). Although it's a nice idea, most evidence suggests that further increases in the minimum wage will do little toward fulfilling this idyllic vision. Minimum wages have proven to be almost entirely ineffective in combating poverty, and, in many cases, raising minimum wage has been proven to increase poverty by contributing to unemployment and inflation. The flaw in the logic resides in the fact that money, as they say, does not grow on trees. By the very same reasoning in favor of raising the wage floor, one might be persuaded to believe that a minimum wage of a million dollars an hour would be a good idea as a means of fighting poverty. After all, if the minimum wage were a million dollars, we would all be millionaires, right? Perhaps a minimum wage of a million dollars would make us all millionaires, but it would be with the added caveat of a nearly useless currency. In this scenario, even a millionaire would likely be considered severely impoverished. Although the example is clearly extreme, it provides a fitting hyperbole for the problems arising from any form of minimum wage, most importantly: where does the extra money come from? Increases in minimum wage have proven to be ineffective because they put stress on employers, which is passed on to everyone else in the form of staff cuts, shorter hours, and more expensive goods and services. When the minimum wage is increased, there is--quite clearly-- no automatic, corresponding increase in a business's revenue. It's hard to imagine the owner of a restaurant, or any other small business owner, advocating for an increase in the wage floor. For example, say your business generates $200,000 a year in revenue, $100,000 of which goes toward paying your employees, and suddenly, the minimum wage is increased by two dollars. Now you have to put $120,000 toward paying your employees, but that sends you over your budget. Your only options are to increase your revenue somehow, cut supply costs, fire someone, or decrease the hours of your employees. Increasing revenue is obviously the most appealing, but it is also the least realistic. More often than not, the employees end up suffering from the same economic woes inflicted upon their employers. Numerous studies have shown that increases in minimum wage have actually exacerbated poverty by generating widespread lay-offs and shift reductions. In a study of single mothers, a ten percent increase in minimum wage was associated with an 8.8 percent reduction in employment, an 11.8 percent reduction in annual hours worked, and almost no net effect on average wages amongst this particular population (Sabia 849).  <center> [Image Source](http://static1.businessinsider.com/image/552bd2d869bedd6258bd511f-2400)</center> Not only do wage minimums cause businesses to thin out their numbers, they also force businesses to hire only the most experienced, efficient, and likable people. The value of the modern employee is raised superficially by the increased cost to the business, and as a result businesses must be more selective in their hiring process. In the words of William Dunkelberg in his article for Forbes magazine, “Raising the minimum wage raises the hurdle a worker must cross to justify being hired” (Dunkelberg 1). Make the hurtle a stepping stone, and the economy will flourish, but raise it up too high, and very few people will make the jump. The job competition, even for the lowest-paying jobs, is often so fierce that less educated or less skilled citizens have no chance at a job in their vicinity. If you have ever looked at a homeless person and thought “get a job,” you may have also thought, subconsciously or otherwise, “I would never hire that person.” Likewise, businesses are becoming less and less willing to train new, unskilled, unkempt, or uneducated employees, preferring to hire only those with an appropriate resumé who can start performing tasks efficiently in the shortest possible amount of time. Of course, this has always been the case to an extent, but the lower the wage minimum, the more freedom businesses have to create jobs of all shapes and sizes. A low or non-existent wage minimum makes it less risky for a business to take a chance on an uneducated or inexperienced applicant, and the previously unemployed can use these menial, less-desirable jobs as a stepping stone to more rewarding opportunities. Unemployment and devalued currency are the surest routes to poverty, and wage minimums contribute to both. Those who would argue for minimum wage increases obviously believe that the higher wages will directly benefit the poor, but as William Dunkelberg points out, “About 60% of the officially poor don’t work, so the only thing raising the minimum wage does for them is to make it harder for them to get a job if they ever decide they want one” (Dunkelberg 1). As for the remaining 40%, an increase in the minimum wage still might not be very helpful. If they aren't laid off, inflation and shift reductions will be sure to take a hefty toll on the breadth and value of their wealth. There is a direct correlation between the increasing height of minimum wage and the inflation of the U.S. Dollar. The two have been growing side by side for decades. One might argue that the minimum wage is a response to (and not a factor in) the rate of inflation, but this view seems to reject the simple logic of our hypothetical “million-dollar minimum wage” scenario. The value of a dollar is a function of several factors, perhaps most importantly: the amount of work required to earn said dollar. If the value of a generic task rises from $7.50 an hour to $10.50 an hour, without any change in the task itself, then it makes perfect sense to assume that the value of a dollar would decrease accordingly. In addition, as was stated earlier, businesses have very few means of recouping the expenses brought on by increases in the minimum wage. Once they have exhausted their options in terms of reducing hours and firing inefficient employees, the only remaining option is to find a way to increase revenue, usually by marginal additions to the price of services. For a hypothetical example, imagine a sandwich shop changing the price of their signature sandwich from seven dollars to eight after the minimum wage jumps a dollar. Perhaps the loyal costumers will keep buying the sandwich or perhaps not, but either way, a small part of the American market has grown more expensive without any change in substance, and thus, inflation has been marginally increased in proportion to the additional expenses brought about by a higher minimum wage. If all of this conjecturing has been unpersuasive, the track record of minimum wage increases should speak for itself. Of the many studies on the effects of these wage-hikes, the majority have found them to be counter-productive, ineffective, or only marginally effective. A 2005 study by Page, Spetz, and Millar found that a ten percent increase in minimum wage was associated with 1 to 2 percent increase in welfare caseloads, which they postulated as evidence for a corresponding increase in poverty (Sabia 850). Burkhauser, Couch, and Wittenberg published a paper in 2000, titled Who Minimum Wage Increases Bite: An Analysis Using Monthly Data from the SIPP and the CPS, in which they wrote, “If modest increases in the minimum wage have no employment effects, then the appropriateness of this method in helping the working poor is strictly a distributional issue. However, if minimum wage increases reduce employment and if the jobs lost are concentrated among the vulnerable groups the policy claims to assist, then policy makers must consider this unintended consequence” (Burkhauser 16-17). They go on to conclude that these increases do, indeed, “significantly reduce employment,” specifically among teenagers and young black adults, presumably two of the more likely candidates to benefit from such legislation (Burkhauser 17). The row of detrimental dominoes is plain to see. Wage increases hurt the business by driving up their employment expenses, and those businesses pass it on by reducing their staff, reducing shift hours, and raising their prices. The newly unemployed, or those with too few shift-hours to live on, enter into an increasingly desolate job market. There are fewer positions available, and the responsibilities and standards for the available positions are more difficult to fulfill. Meanwhile, the dollars they have been working so hard to attain continue to steadily lose their value. References: Burkhauser, Richard V., Kenneth A. Couch, and David C. Wittenburg. "Who Minimum Wage Increases Bite: An Analysis Using Monthly Data from the SIPP and the CPS." Southern Economic Journal (2000): 16-40. Web. 9 Apr. 2014. Couch, Kenneth A., and David C. Wittenburg. "The Response of Hours of Work To Increases in the Minimum Wage." Southern Economic Journal (2001): 171-77. Web. 8 Apr. 2014. Dunkelberg, William. "Why Raising The Minimum Wage Kills Jobs." Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 31 Dec. 2012. Web. 08 Apr. 2014. Rugy, Veronique. "Raising the Minimum Wage: A Tired, Bad Proposal." National Review Online. N.p., 13 Feb. 2013. Web. 09 Apr. 2014. Sabia, Joseph J., and Richard V. Burkhauser. "Minimum Wages and Poverty: Will a $9.50 Federal Minimum Wage Really Help the Working Poor?" Southern Economic Journal 76.3 (2010): 592-623. Web. 8 Apr. 2014. Sabia, Joseph J. "Minimum Wages and the Economic Well-being of Single Mothers." Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 27.4 (2008): 848-66. Web. 9 Apr. 2014. Cover Photo: [Image Source](http://cdn07.allafrica.com/download/pic/main/main/csiid/00420447:6b1ad733ef309e9c38e6063957e9c968:arc614x376:w614:us1.png)

👍 pliatusz, hlezama, aaliyahholt, hosgug, opaulo, smelly, cyclope, rojassartorio, agustinars, yris, jhelbich, delicarola, zuzuchain, pachipanda, sponge-bob, bytzz, fullcolorpy, pastorencina, htooms, evelynchavez, gersonpy, steemrant, ordosjc, gabyjc, gracerolon, franciscana23, done, sensation, heberwords, aleor, ysmael20, jennyburgos, bcc, odepasqua,